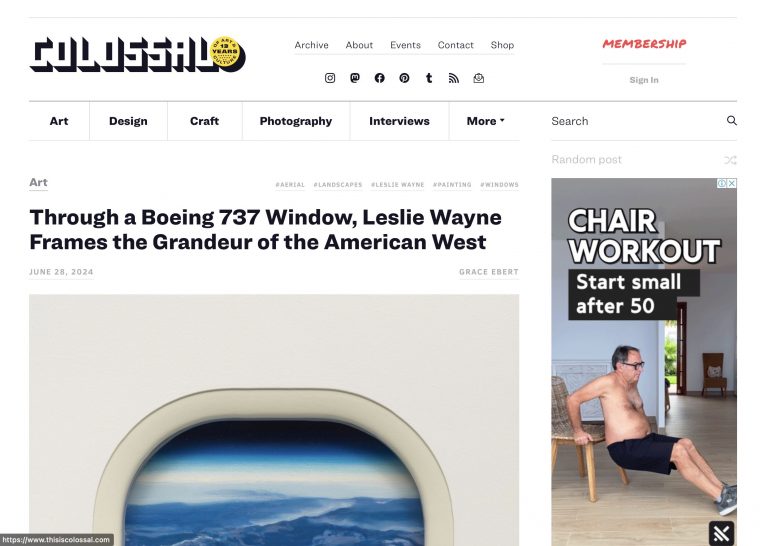

The German word heimat roughly translates to the web of ideas and feelings associated with home and the land we occupy. During a flight across the Rocky Mountains and Cascade Range in 2021, the concept was front and center for artist Leslie Wayne as she peered down through the small airplane window at the massive expanses below…

Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson / Despite the still breathtaking majesty of the physical world, human machinations are undermining its habitability. The United States is more starkly and toxically divided than it has been since the Civil War, and some Americans claim, contra Woody Guthrie, that “This Land” – the title of Leslie Wayne’s cogent new exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery – was made only for them and not for other Americans. This existential double-whammy…

In an evocative exploration of the American West, artist Leslie Wayne’s latest exhibition, ‘This Land,’ is now on view at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York. Through two distinct yet interconnected bodies of work, Wayne investigates the essence of geological space, blending perception with…

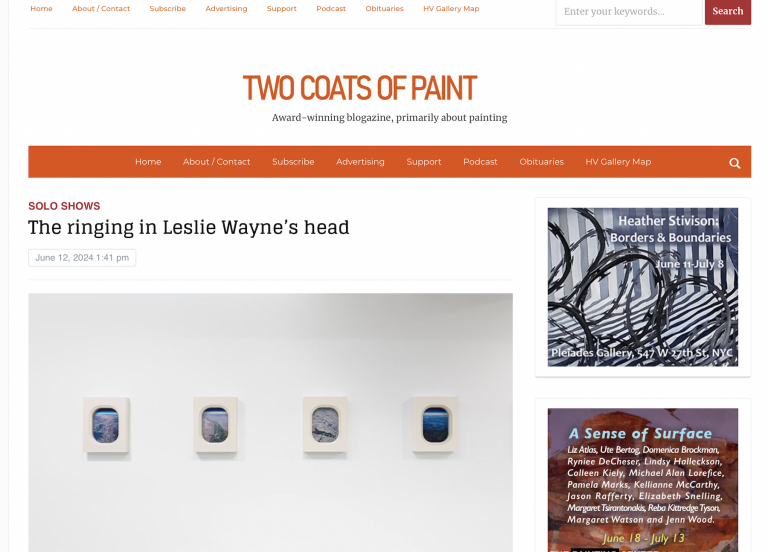

Leslie Wayne is no stranger to windows and portals. Her sculptural oil paintings often take on the subject, including mirrors, doors, closets, or wardrobes, toying with the boundaries between painting, image, and object. As a young painter in California, she focused on plein air landscapes. “I was intent on observation, honing my skill on…

In the painting Everything, 2019, by Leslie Wayne, a set of white, wooden doors hinges outward. A piece of rope looped and knotted through a pair of metal handles seems to be the only measure keeping the contents from bursting through…

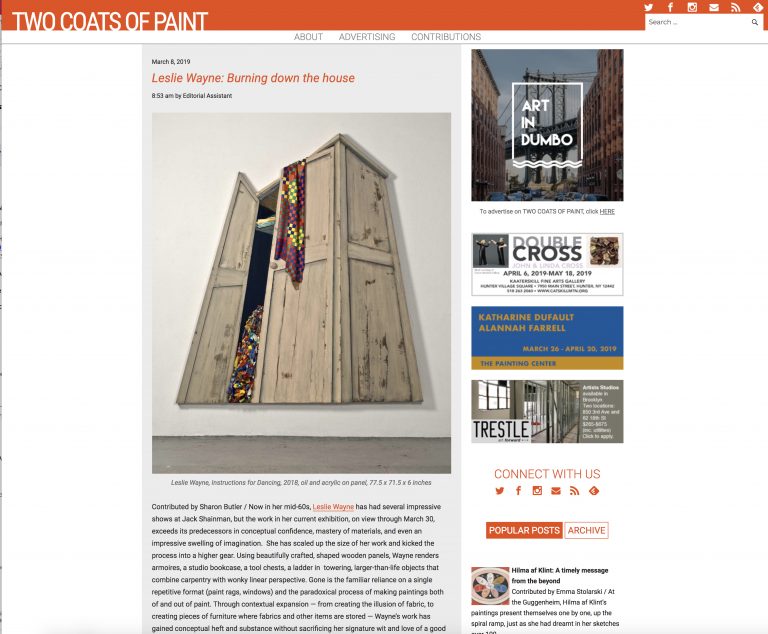

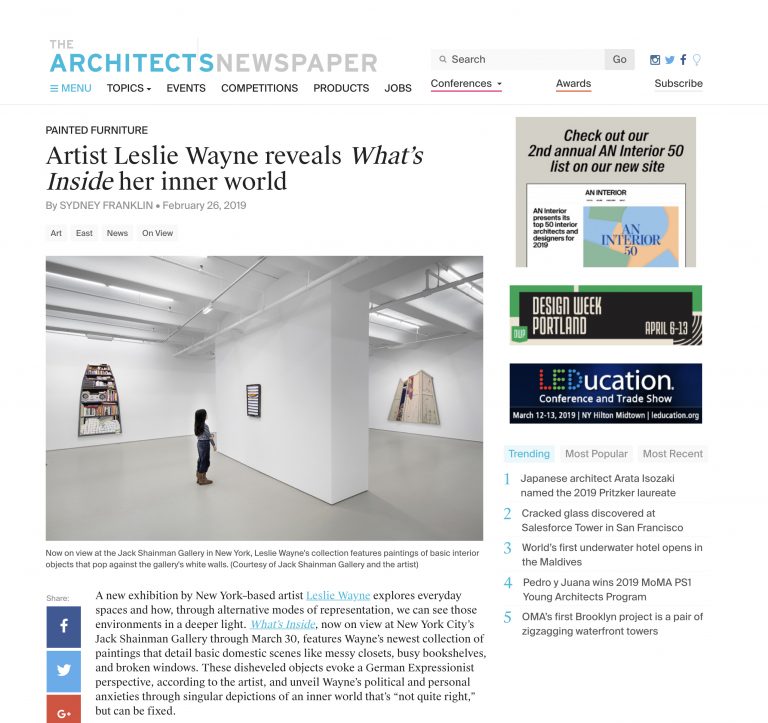

Contributed by Sharon Butler / Now in her mid-60s, Leslie Wayne has had several impressive shows at Jack Shainman, but the work in her current exhibition, on view through March 30, exceeds its predecessors in conceptual confidence, mastery of materials, and even an impressive swelling of imagination…

The architectonics of Leslie Wayne’s structures exude impermanence and a poetic expression of loss….

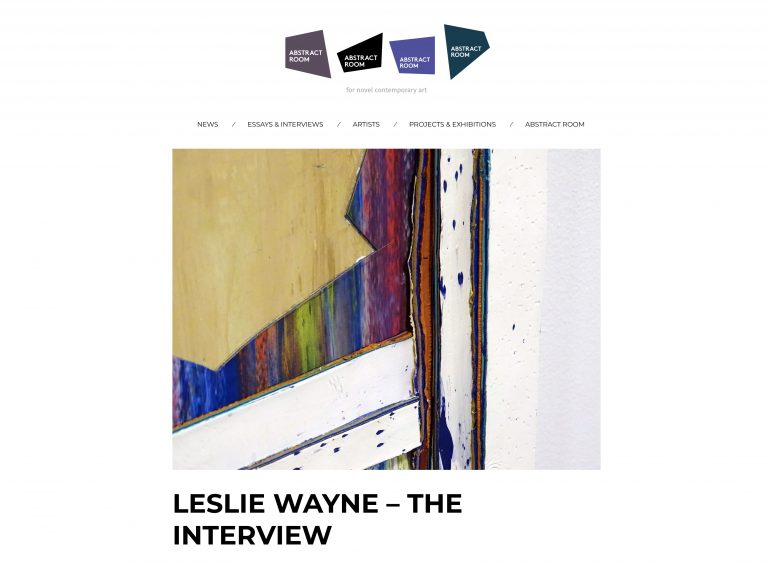

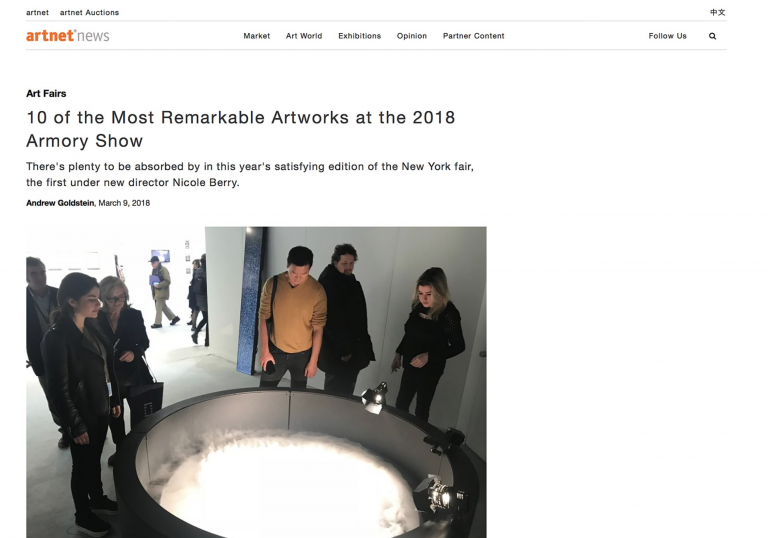

Can you tell us about your last body of work, that you are about to show in a solo presentation at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City?…

A new exhibition by New York–based artist Leslie Wayne explores everyday spaces and how, through alternative modes of representation, we can see those environments in a deeper light…

Leslie Wayne was born in 1953 in Landstül, Germany to American parents and grew up in Southern California.

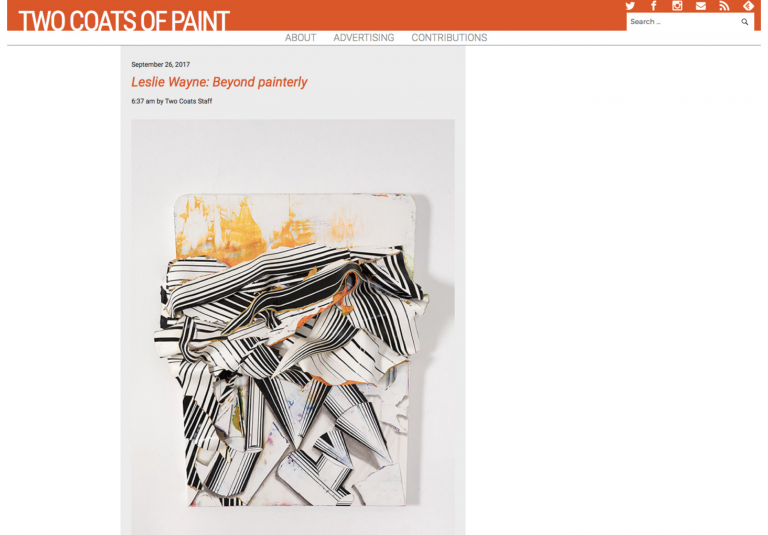

It took the painter Leslie Wayne years and years to perfect her unique style of layering acrylics and oils until they become objects themselves—and not merely trompe-l’oeil ones—by convincingly imitating draped fabrics and boards of wood. However, while she was able to pull off individual objects convincingly, she never managed to make a larger painting that could fuse her motifs… until now.

Leslie Wayne’s richly layered paintings remind us of the playfulness and emotional range to be found in abstraction.

Leslie Wayne has upped her painterly game considerably. Her new small-scale works shine in spectacularly complex and layered ways, becoming pictures, still-lifes, landscapes, paintings, and things that are more than “about” things. —J.S

Contributed by Sharon Butler and Jonathan Stevenson / Leslie Wayne, in transcendently clever new work on view at Jack Shainman Gallery through October 21, has encapsulated a significant strand of art history. Renaissance artist Leon Battista Alberti is often credited with the observation that a painting is a window through which to see the world. That was in the 1400s. In 1920, Marcel Duchamp drew up plans for a scaled-down French window, had it constructed by a carpenter he knew out of wood, glass, and paint, and outfitted it with panes made of black leather. He insisted that the leather be polished every day to prevent any kind of illusion from arising in the work. Duchamp’s dark, depthless window was a snarky riff on Alberti’s supposed comment: a painting may be a window, but a window need not illuminate anything much at all. As obtuse and sardonic as Duchamp may have been, he had still done painting the enduring service of bringing the picture more immediately into the physical space of the viewer

Contributed by Sharon Butler and Jonathan Stevenson / Leslie Wayne, in transcendently clever new work on view at Jack Shainman Gallery through October 21, has encapsulated a significant strand of art history. Renaissance artist Leon Battista Alberti is often credited with the observation that a painting is a window through which to see the world. That was in the 1400s. In 1920, Marcel Duchamp drew up plans for a scaled-down French window, had it constructed by a carpenter he knew out of wood, glass, and paint, and outfitted it with panes made of black leather. He insisted that the leather be polished every day to prevent any kind of illusion from arising in the work. Duchamp’s dark, depthless window was a snarky riff on Alberti’s supposed comment: a painting may be a window, but a window need not illuminate anything much at all. As obtuse and sardonic as Duchamp may have been, he had still done painting the enduring service of bringing the picture more immediately into the physical space of the viewer

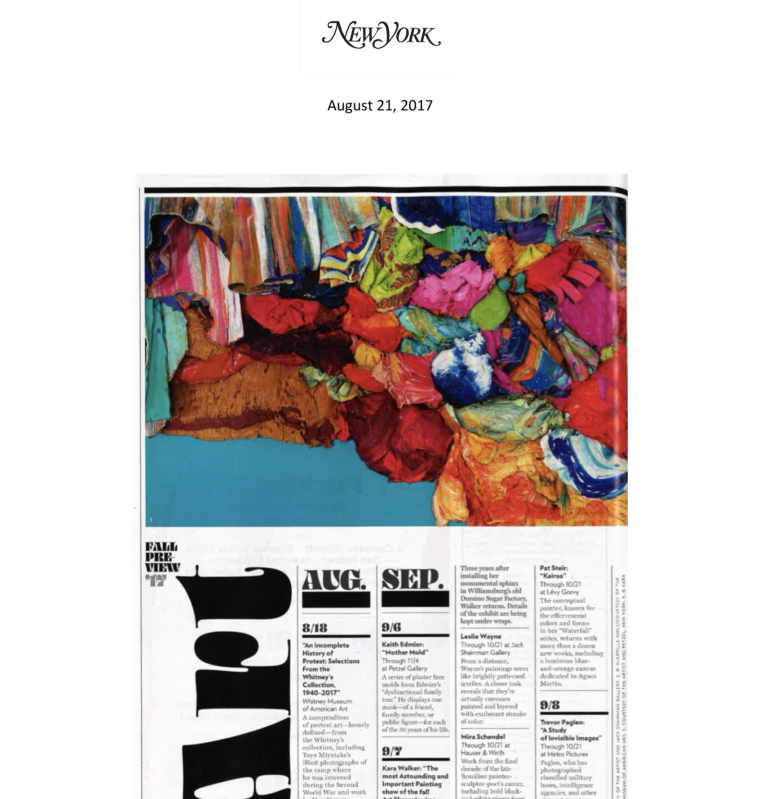

“Fall Preview” New York Magazine, page 120, August 21, 2017

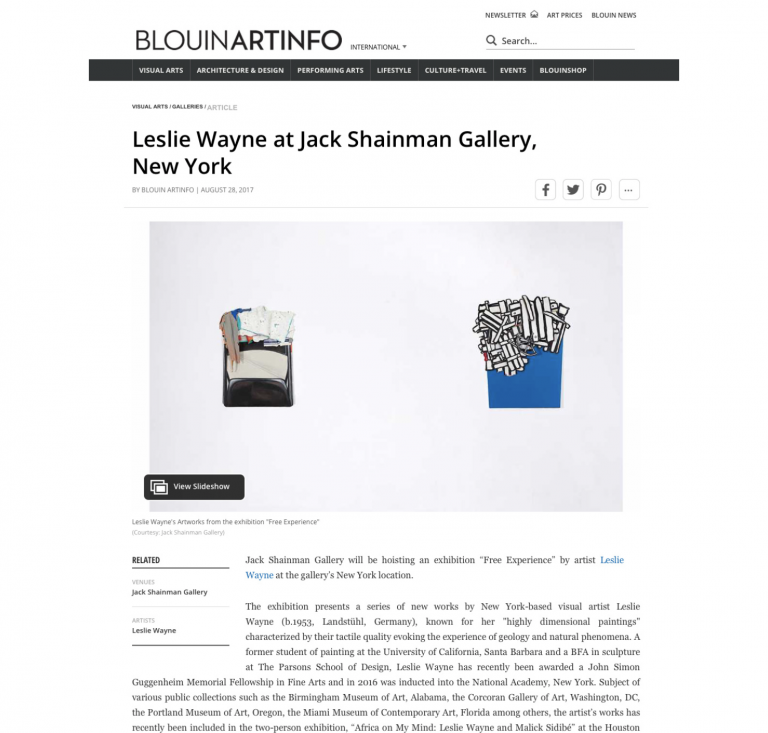

Jack Shainman Gallery will be hoisting an exhibition “Free Experience” by artist Leslie Wayne at the gallery’s New York location

Jack Shainman Gallery will be hoisting an exhibition “Free Experience” by artist Leslie Wayne at the gallery’s New York location

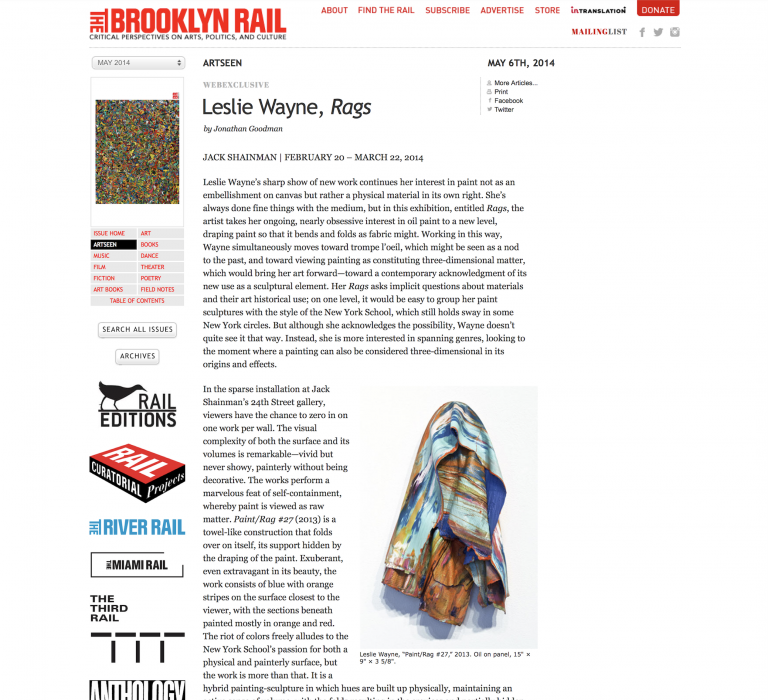

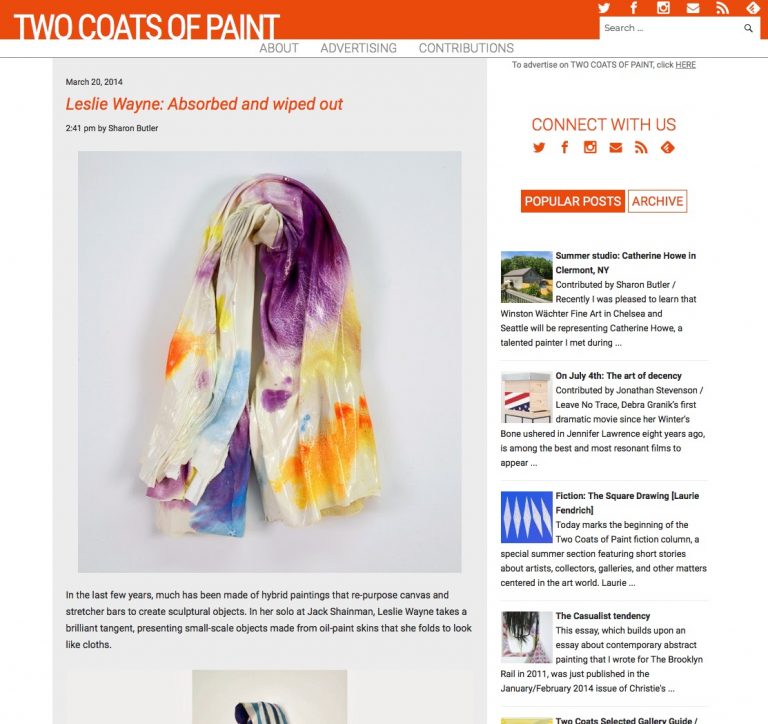

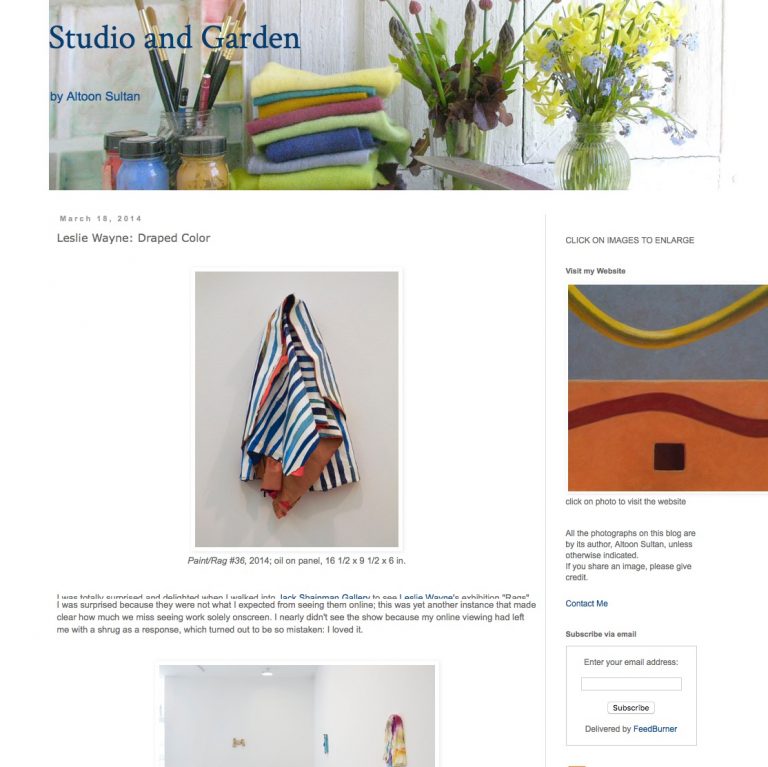

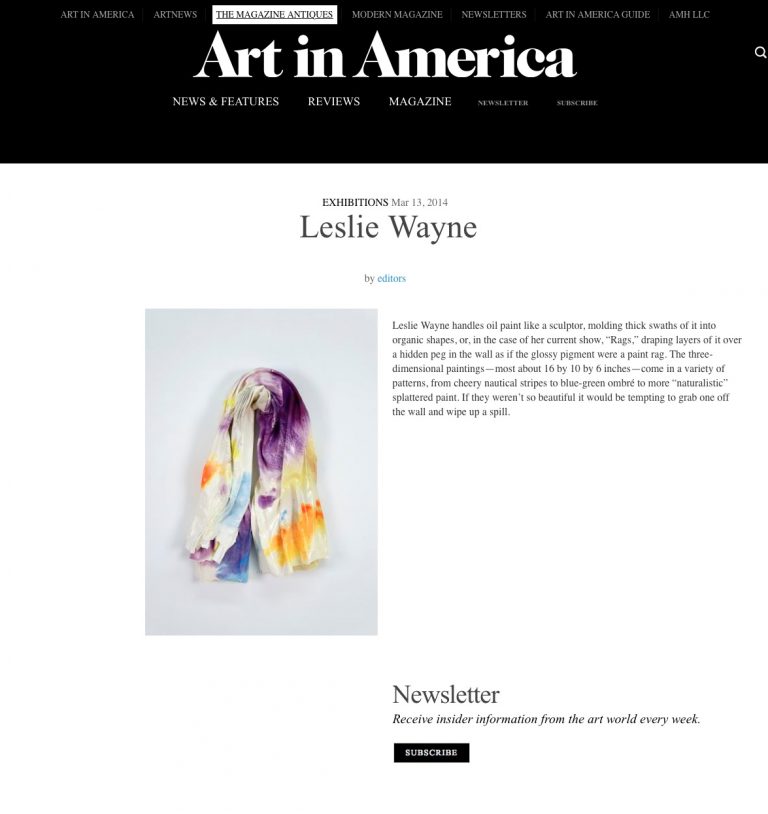

Leslie Wayne united the mediums of painting and sculpture in this elegant and cerebral show of eleven painted “studio rags.”

The past seasons grim weather made visiting NY windswept Chelsea

Leslie Wayne’s sharp show of new work continues her interest in paint not as an embellishment on canvas but rather a physical material in its own right.

I was totally surprised and delighted when I walked into Jack Shainman Gallery to see Leslie Wayne’s exhibition “Rags”.

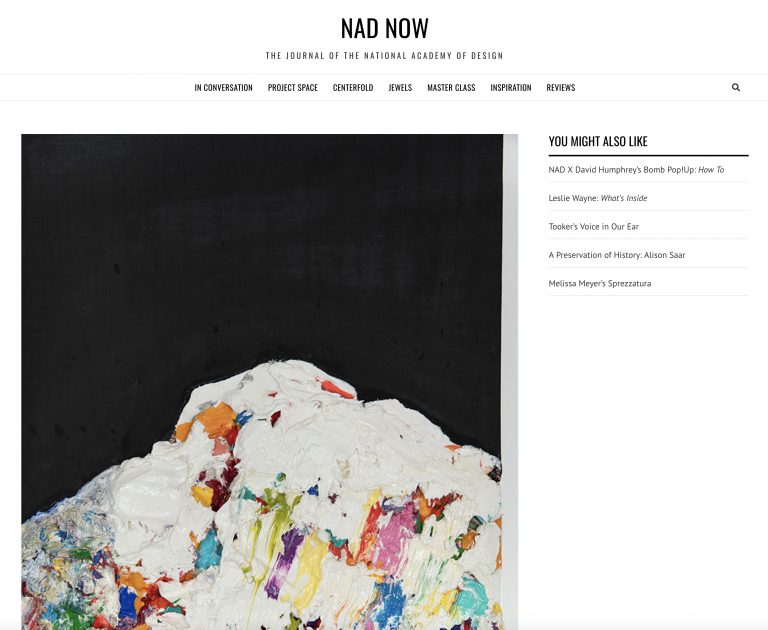

Leslie Wayne handles oil paint like a sculptor, molding thick swaths of it into organic shapes, or, in the case of her current show, “Rags,

Wayne manipulates the medium of painting by approaching oil paint as a sculptural material.

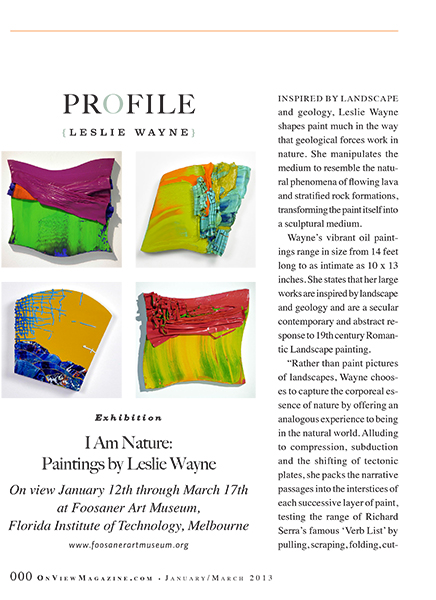

INSPIRED BY LANDSCAPE and geology, Leslie Wayne shapes paint much in the way that geological forces work in nature. She manipulates the medium to resemble the natural phenomena of flowing lava and stratified rock formations, transforming the paint itself into a sculptural medium. (page 114-115)

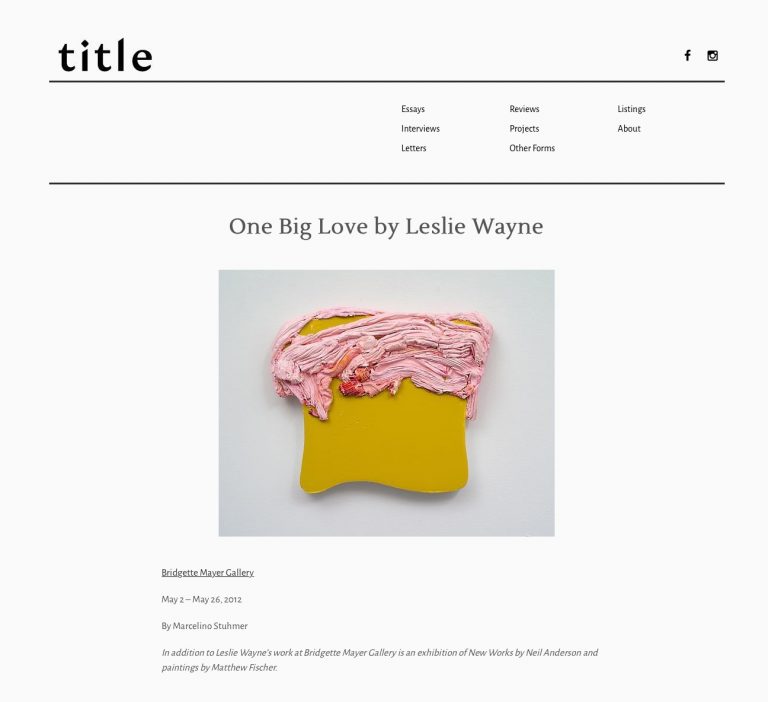

The current three-some of painters at Bridgette Mayer Gallery ask how many ways a painting can be abstract. Works in the large galleries pair Leslie Wayne’s small sculptural paintings and Neil Anderson’s large lyrical topographies. While Wayne is interested in using paint as a sculptural material, Anderson’s work reinforces paint’s flatness. Matthew Fischer, in the Vault, presents work that is between these two extremes.Wayne’s “One Big Love #50” from 2010 encapsulates many of the ideas that are central to the artist’s work. The poured field of paint is a nod to Helen Frankenthaler and the history of Abstract Expressionism, but Wayne pours a thick layer that rejects the AbEx emphasis on flatness.”

Whether ironic or sentimental, silly or heart wrenching, Leslie Wayne’s new series of small 10 X 13 inch works on shaped panels deserve close attention. She doesn’t really paint so much as fold and twist thick pastes of oil paint to explore the materiality and processes of the medium in relationship to natural and sculptural forces. The work displays a playful poetics of unconscious fears and desires. Wayne creates an uncanny interpretive relationship between inextricable performances of material on shaped surfaces, the objects of painting and the paintings’ objecthood, and between the artwork and the viewer.”

I don’t recall hearing the phrase “I am an abstractionist” recently. The term abstraction conjures up recollections of a driving force against immobile academicism. Artists as individuals no doubt eschew any categorization and often abstraction is perceived as a kind of hard-core formalism linked solely to the notion of purity.

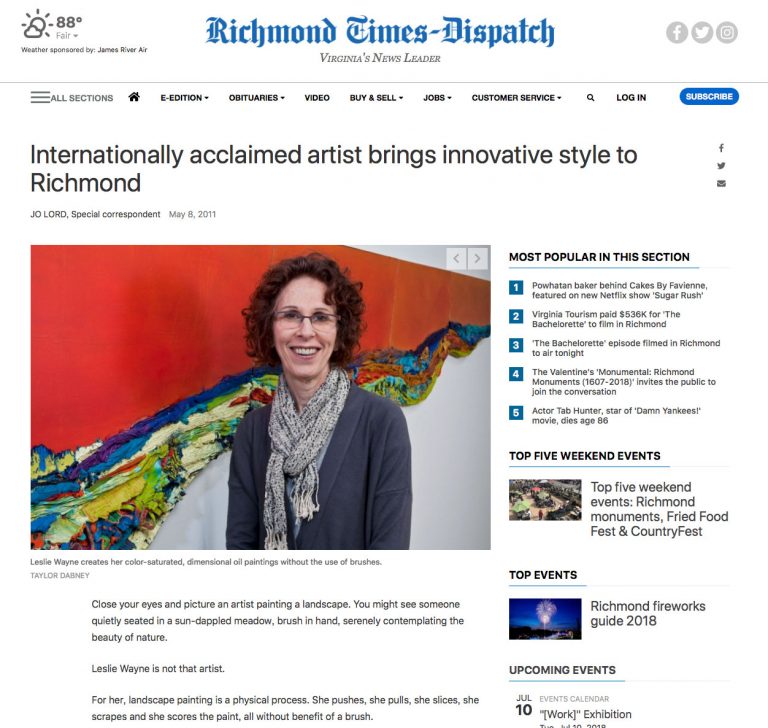

Leslie Wayne studied traditional oil painting, and then switched to sculpture at the Parsons School of Design. Later, she transitioned back to painting, but the Parsons years left their mark. “The experience of making sculpture had a big impact on the way I think about making paintings,” Wayne said in an interview from her home in New York City, where she lives with her husband, sculptor Don Porcaro. “Paintings don’t have to be a flat illusion of a three-dimensional world. They can be three-dimensional themselves. They can be built the way you build anything.”

Close your eyes and picture an artist painting a landscape. You might see someone quietly seated in a sun-dappled meadow, brush in hand, serenely contemplating the beauty of nature. Leslie Wayne is not that artist. For her, landscape painting is a physical process. She pushes, she pulls, she slices, she scrapes and she scores the paint, all without benefit of a brush. The result — a dynamic collection of color saturated, dimensional oil paintings — is on view at the Visual Arts Center of Richmond.

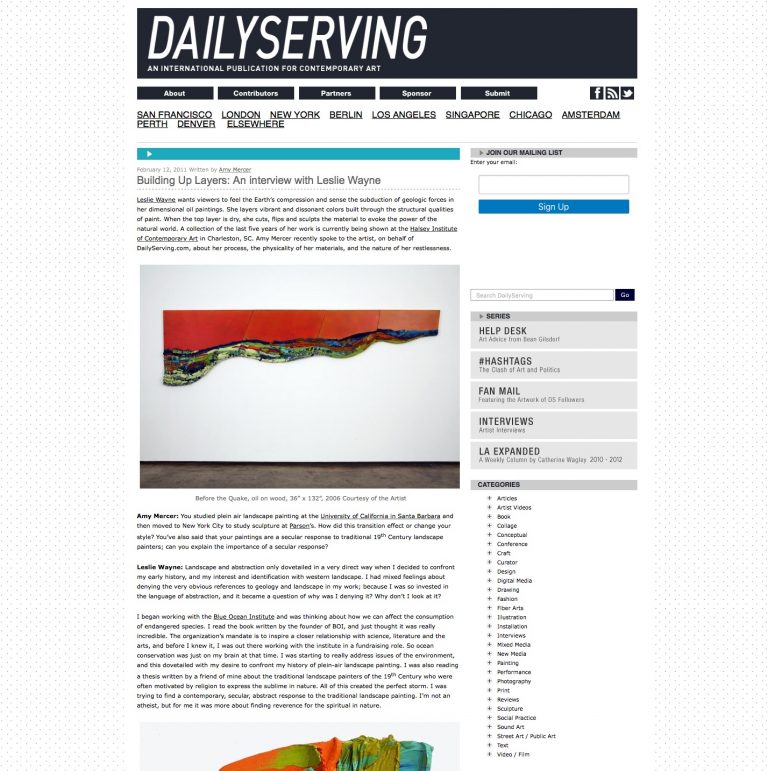

Leslie Wayne wants viewers to feel the Earth’s compression and sense the subduction of geologic forces in her dimensional oil paintings. She layers vibrant and dissonant colors built through the structural qualities of paint. When the top layer is dry, she cuts, flips and sculpts the material to evoke the power of the natural world. A collection of the last five years of her work is currently being shown at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art in Charleston, SC. Amy Mercer recently spoke to the artist, on behalf of DailyServing.com, about her process, the physicality of her materials, and the nature of her restlessness.

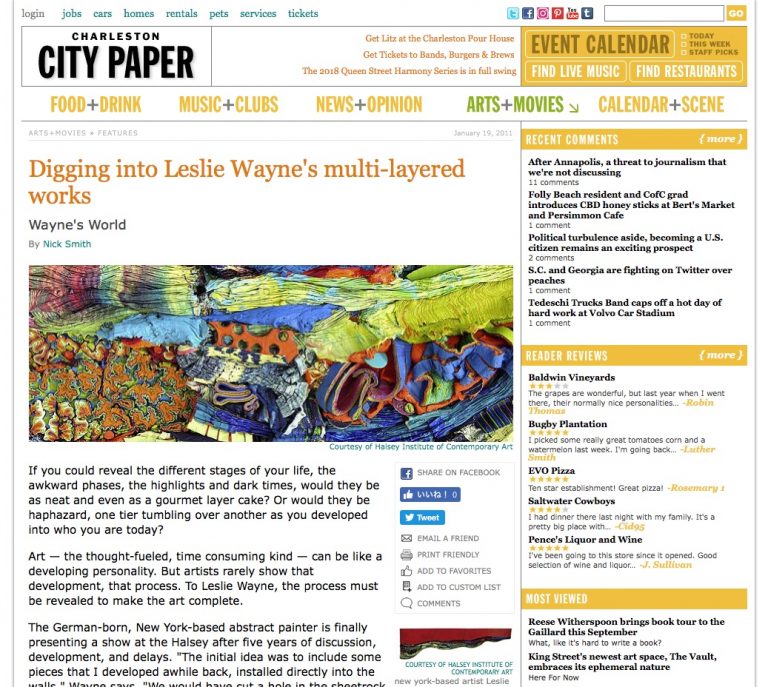

If you could reveal the different stages of your life, the awkward phases, the highlights and dark times, would they be as neat and even as a gourmet layer cake? Or would they be haphazard, one tier tumbling over another as you developed into who you are today?

Art — the thought-fueled, time consuming kind — can be like a developing personality. But artists rarely show that development, that process. To Leslie Wayne, the process must be revealed to make the art complete.

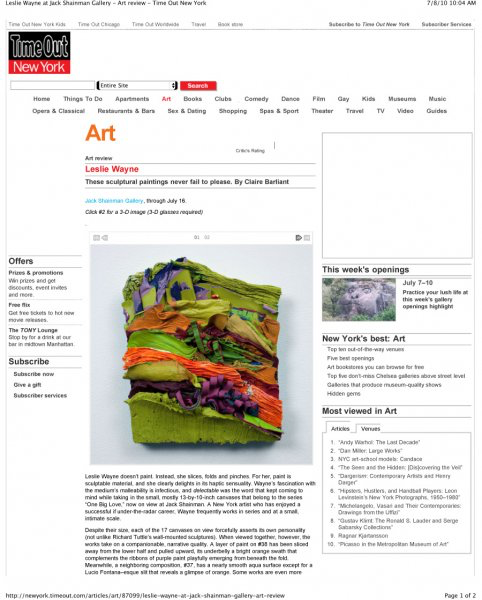

Leslie Wayne doesn’t paint. Instead, she slices, folds and pinches. For her, paint is sculptable material, and she clearly delights in its haptic sensuality. Wayne’s fascination with the medium’s malleability is infectious, and delectable was the word that kept coming to mind while taking in the small, mostly 13-by-10-inch canvases that belong to the series “One Big Love,” now on view at Jack Shainman. A New York artist who has enjoyed a successful if under-the-radar career, Wayne frequently works in series and at a small, intimate scale.

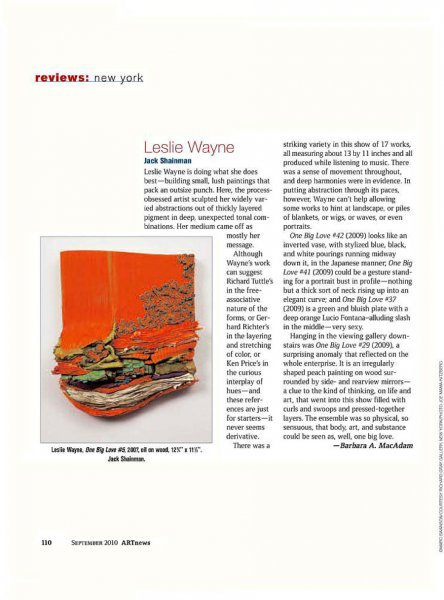

Leslie Wayne is doing what she does best-building small, lush paintings that pack an outsize punch. Here, the process-obsessed artist sculpted her widely varied abstractions out of thickly layered pigment in deep, unexpected tonal combinations.

Can the two artists in a couple be identified based on the artwork they create? That is the question behind “Couples,” the exhibition currently at the Islip Art Museum. More than just an art show, it is a parlor game.

Marriage is often described as “Work” – a project of compromise and compassion. So how do two artists, those avatars of individualism, function as members of a couple? Does each entertain envy for the other’s success? Do they influence each other’s styles, or get on each other’s nerves? Does a husband seek inspiration from a wife or does he deliberately turn away, afraid of her influence?

Wayne’s language is a subtle fusion of reductivist formalism and romantic expressionism, while Porcaro’s is early 20th century totemic abstraction, biomorphic surrealism and Pop art. They Levitra Online show a conceptual concern with ceremony in the process of making their art, but from different historical perspectives. The energy of both artists is a consequence of acknowledgement of their precursors and their ability to supersede these influences without abandoning them completely.

In her characteristic process, Leslie Wayne scrapes forward, gouges through, and peels back layers of paint that she has gradually applied over weeks or even months. For the remarkable new work shown here, she followed the same practice by confined her activity to a corner of each of the canvases—which, in the meantime, have grown bigger. The shift in scale has resulted in works that appear both more restrained and more playful, the corner flourishes providing teasers of what might be.

It’s always fun to see the clever ways in which an artist known primarily for her work in another medium first translates her ideas into print. Lesley Wayne is known for her paintings in very high relief, in which the paint is raised in thick layers off the surface of the support. For this screen-print, she blew up and cut out photographs of paint, then hand-separated the images. The separated colors were printed in four eight-color layers in the lower left corner of a transparent white field of unregistered and separated screens.

The painter Leslie Wayne and her husband, sculptor Don Porcaro, combined their very different works in this delightfully sympathetic show. They defined it as two solos—she called hers “Love in the Afternoon” and he called his “Oracle”—but they occupied the same gallery and each gained something from the other’s presence. Here both artists worked smaller than usual, and each showed 60 recent pieces.

Enter the modest-sized gallery that houses the joint exhibitions titled “Oracle” by sculptor Don Porcaro, and “Love in the Afternoon” by painter Leslie Wayne, and the whole room invites you to frolic in a quazi-Dadaist landscape bristling with kinetic energy.

Paintings don’t come much thicker than Ms. Wayne’s. The artist layers paint into two-inch deep boxes and then gouges into the still-wet oil with instruments or her hands, producing deep, multicolored gashes. In a whole-wall piece, scattered punctures and slashes colorfully bleed; the effect is at once prettily decorative and viscerally violent.

Leslie Wayne’s clever intra-sheetrock works –paintings that seem to erupt from the gallery wall like wounds spewing gobs of paint – are often more tantalizing as an idea than as the objects assembled at Midtown’s Solomon Projects. Subverting the integrity of the gallery’s pristine white cube and blurring the line between painting, and installation, the majority of Wayne’s works in Under my Skin appear to short circuit the usual commercial exchange of cash for art.

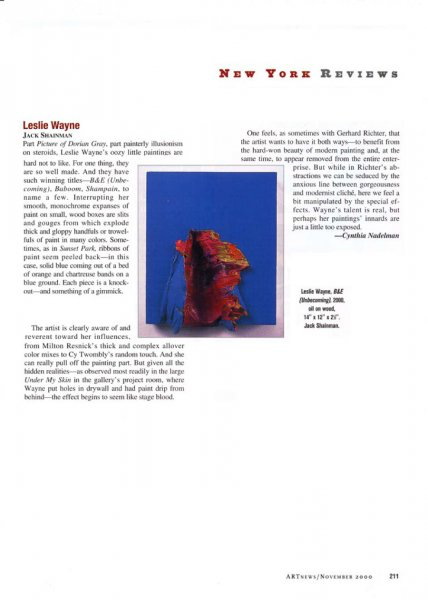

Leslie Wayne’s oozy little paintings are hard not to like. For one thing, they are so well made. And they have such winning titles. Interrupting her smooth, monochrome expanses of paint on small, wood boxes are slits and gouges from which explode thick and gloppy handfuls of trowelfuls of paint in many colors.

Layers of paint buckle upward or ooze into ridges. They striate into ribbons as thick and unctuous as fat udon noodles. Confined to a quadrant of a small canvas, the strips of paint pleat and pucker and loop over themselves, revealing, underneath, dime-thin strata of outlandishly bright colors. While each of the nine paintings is no longer than a square foot, the desire they incite is vast.

The recent work of New York painter Leslie Wayne at the Haines Gallery is pure comic abstraction: she makes paintings clown. Early abstract paintings had a utopian flavor on which contemporary taste gags. The modern utopias all having backfired, any promise of shining social or personal prospects in art today inspires suspicion.

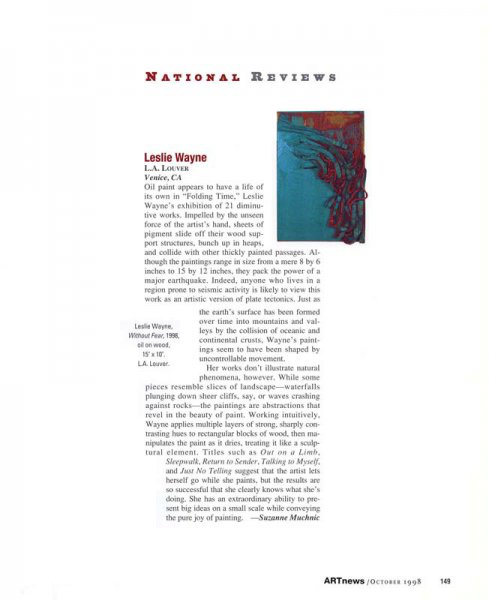

Oil pant appears to have a life of its own in “Folding Time,” Leslie Wayne’s exhibition of 21 diminutive works, impelled by the unseen force of the artist’s hand, sheets of pigment slide off their wood support structures bunch up in heaps, and collide with other thickly painted passages.

Painting has had a rough time; since the end of the 1980s, when the market for neoexpressionalism collapsed and ambitious young artists went back to making installation art. The Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., hasn’t ad it any easier. Attached to an art school filled with typically bumptious art students, it was—in spite of a slightly frumpy collection—long considered by artists to be their kind of open-minded place.

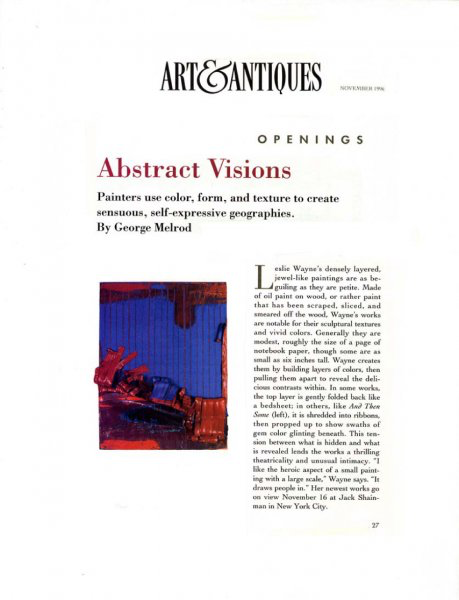

Leslie Wayne’s densely layered; jewel-like paintings are as beguiling as they are petite. Made of oil paint on wood, or rather paint that has been scraped, sliced, and smeared off the wood, Wayne’s works are notable for their sculptural textures and vivid colors.

Leslie Wayne makes diminutive paintings that have the substantial presence of bas-relief. She piles and shapes mounds of oil paint, applied with anything but a brush, to small wood panels. Although Wayne employs traditional compositional devices, the resulting weighty panels usually look quite fresh. The thick passages suggest all sorts of things—drapery, waves, rocks, and pages of an open book—while mostly skirting depiction of recognizable images.

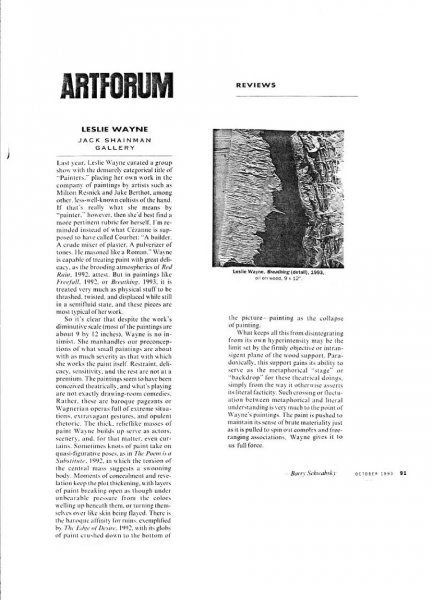

Last year, Leslie Wayne curated a group show with the demurely categorical title of “Painter,” placing her own work in the company of paintings by artists such as Milton Resnick and Jake Berthot, among other, less-well-known cultists of the hand. If that’s really what she means by “painter,” however, then she’d best find a more pertinent rubric for herself. I’m reminded instead of what Cezanne is supposed to have called Courbet; “A builder. A crude mixer of plaster. A pulverizer of tones. He masoned like a Roman.”

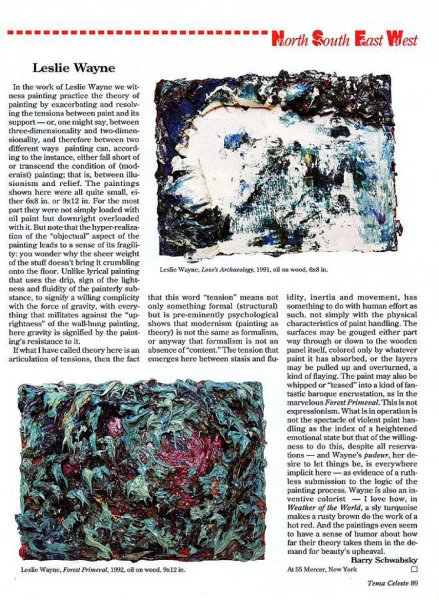

In the work of Leslie Wayne we witness painting practice the theory of painting by exacerbating and resolving the tensions between paint and its support—or, one might say, between three-dimensionality and two-dimensionality, and therefore between two different ways painting can, according to the instance, either fall short of or transcend the condition of (modernist) painting; that is, between illusionism and relief.