Free Experience

When Rosalind Krauss wrote her 1979 essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” (October, Vol. 8., Spring 1979, pp. 30-44), she was making a claim for how infinitely malleable the category of sculpture had become. So malleable in fact that critical historicizing had left the very term sculpture without anchors to the very things that differentiated it from other three-dimensional objects, happenings, installations performances, and the like. Yet in spite of this expanded idea of what it had become, one could never deny, she wrote, that it would always remain a “historically bounded category and not a universal one.” That is, one would always regard sculpture in relationship to the historical precedents set by writers and critics before them who normalized what was new and strange in their time.

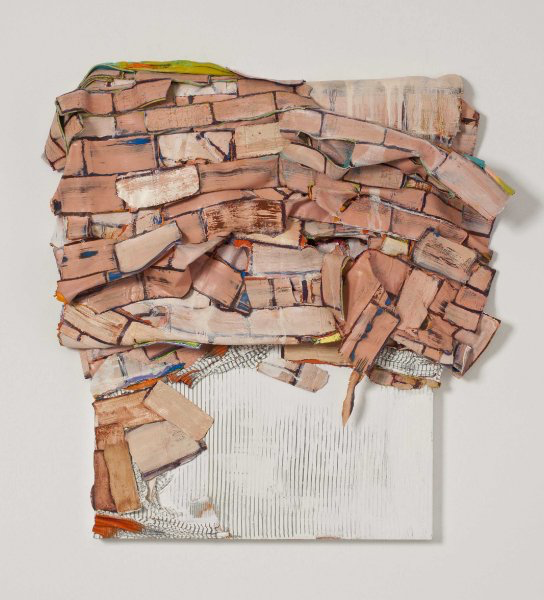

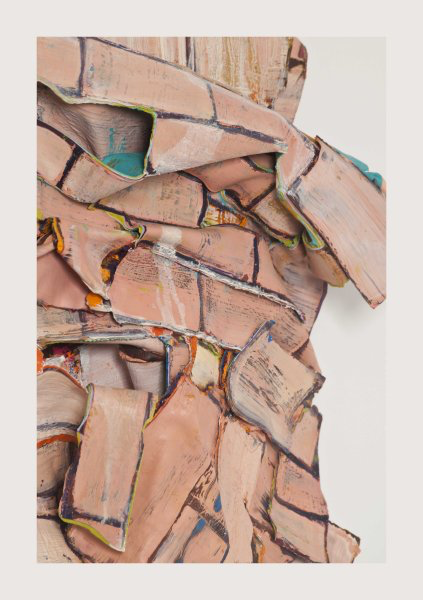

One could make the same claim for painting today, that in spite of the myriad ways that painting currently presents itself, one still considers painting in relationship to its historical precedent, which is a picture on a two-dimensional plain.

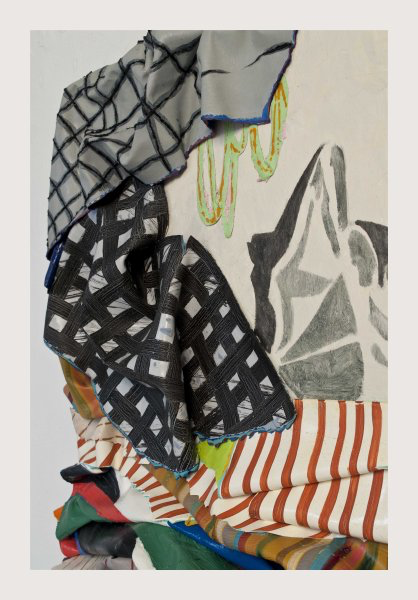

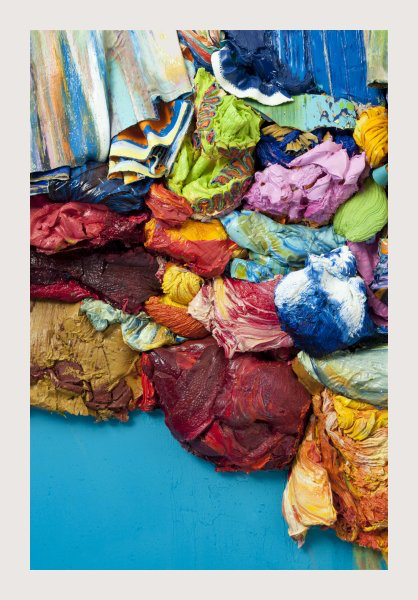

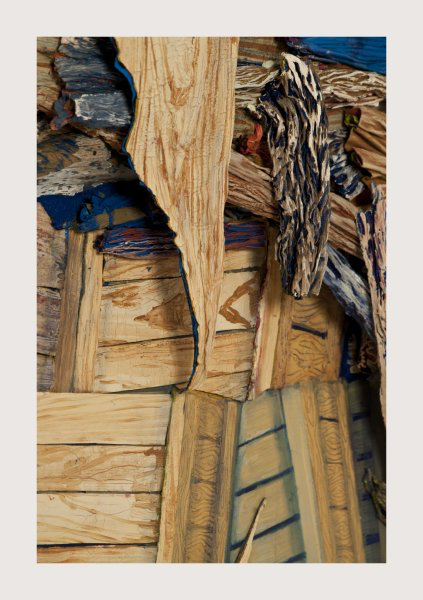

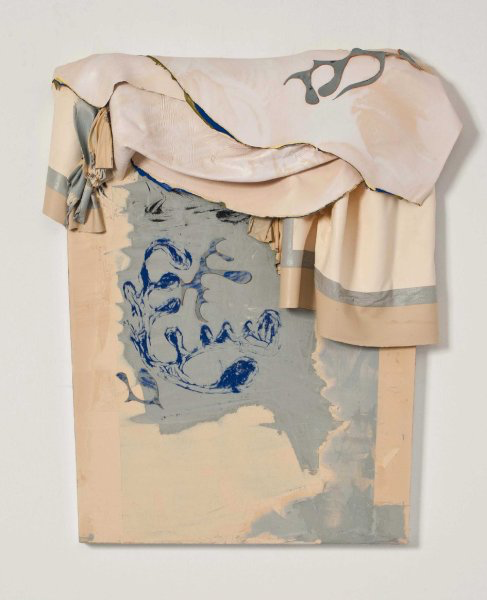

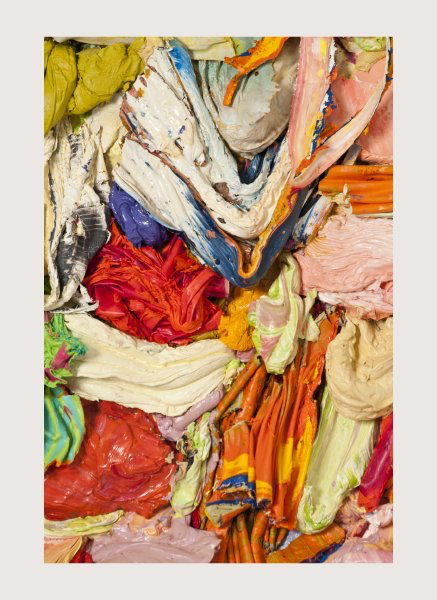

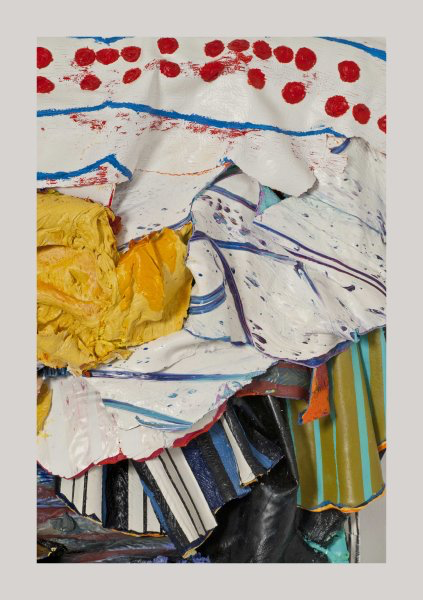

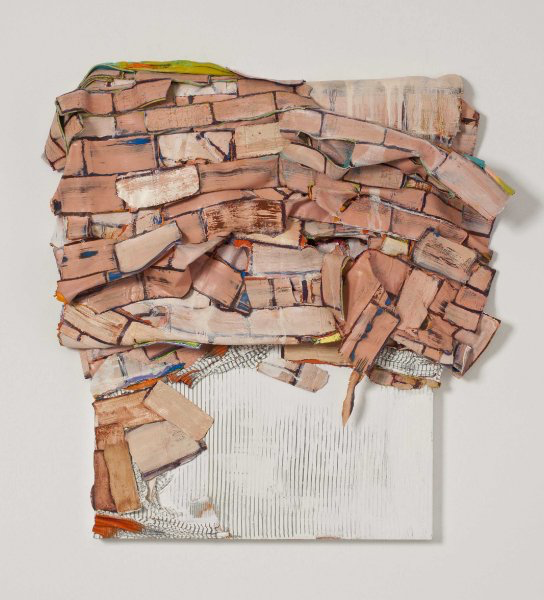

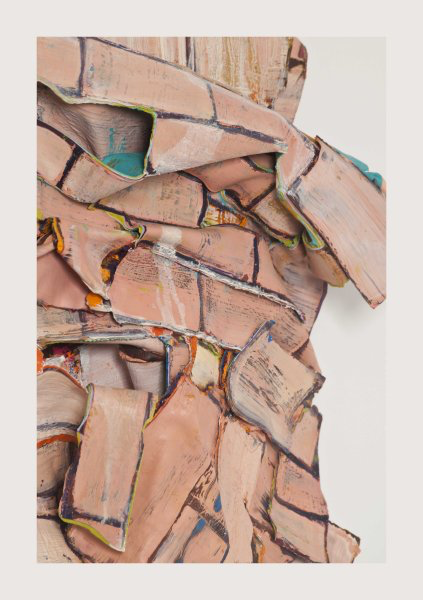

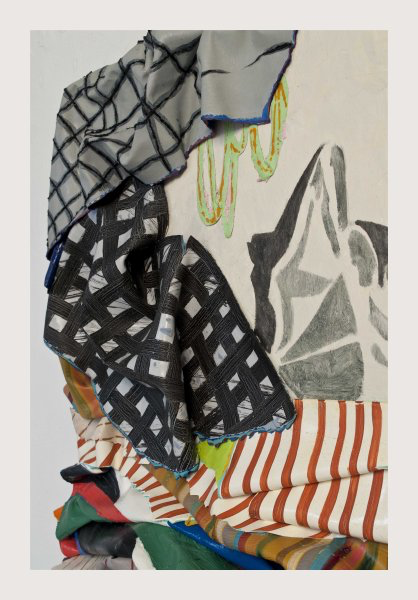

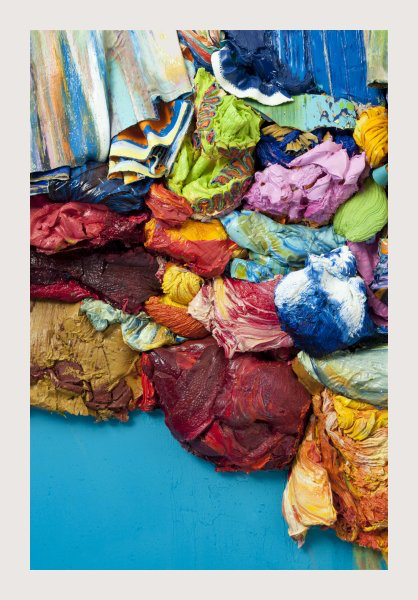

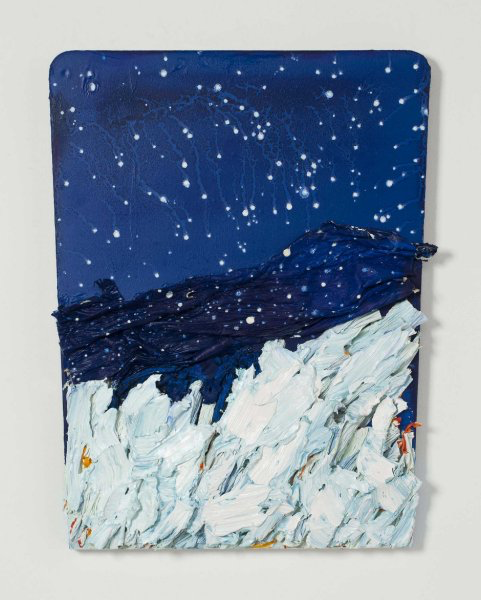

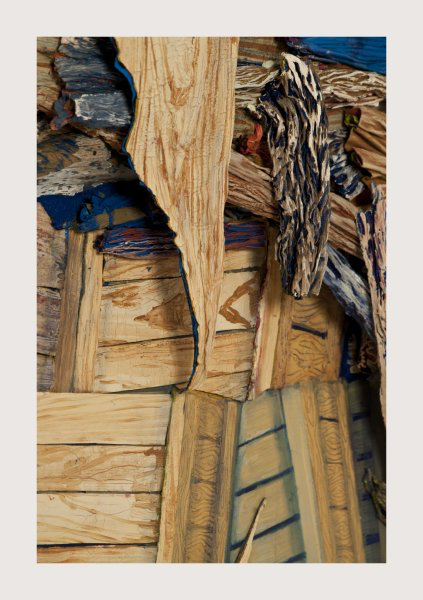

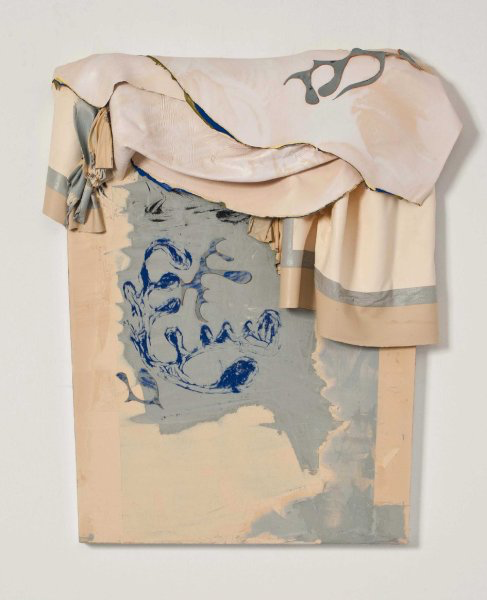

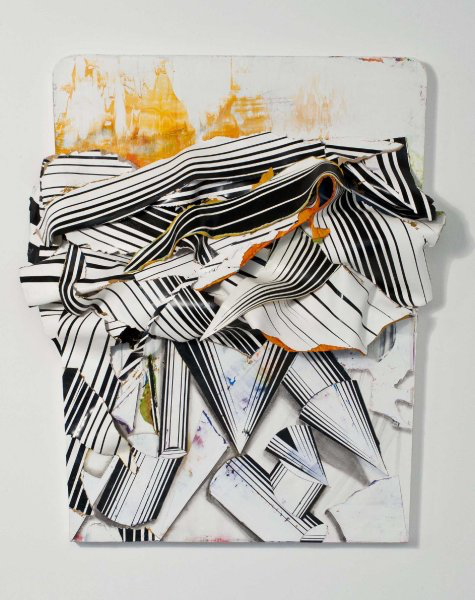

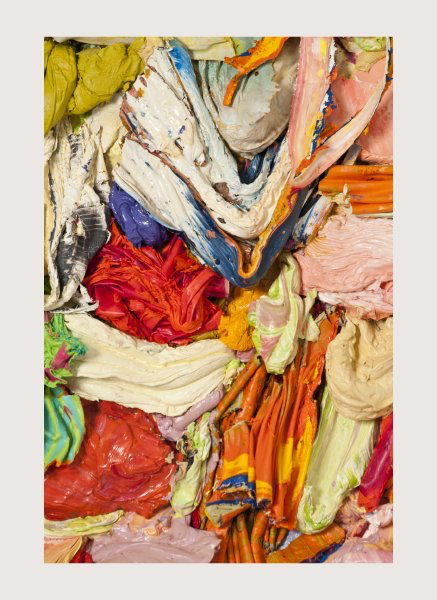

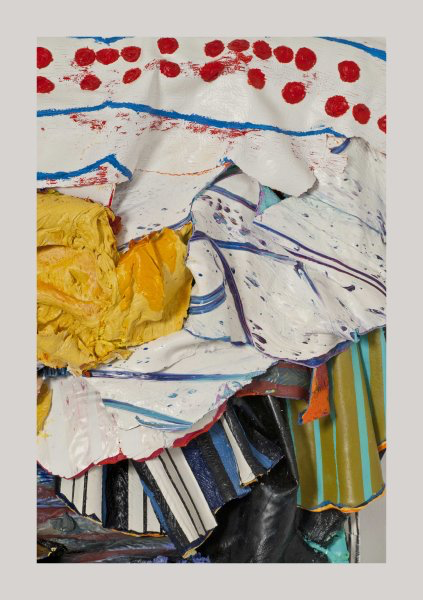

In my last series of work entitled Paint/Rags, I was exploring the ways in which painting as object could force a re-examining of the term painting. The three-dimensional Paint/Rags took the literal form of draped cloth, and became, like readymades, stand-ins for the objects they were representing.

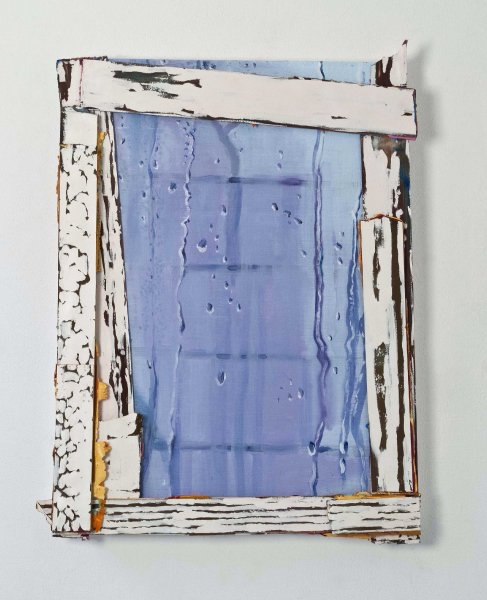

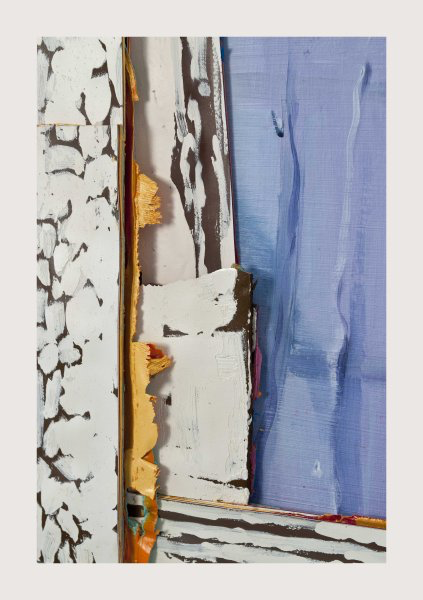

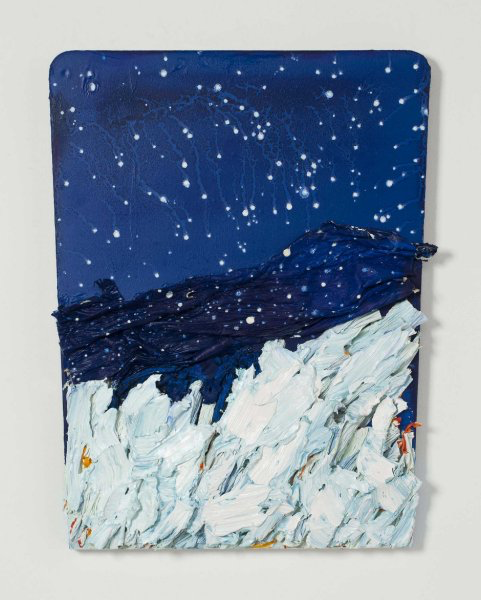

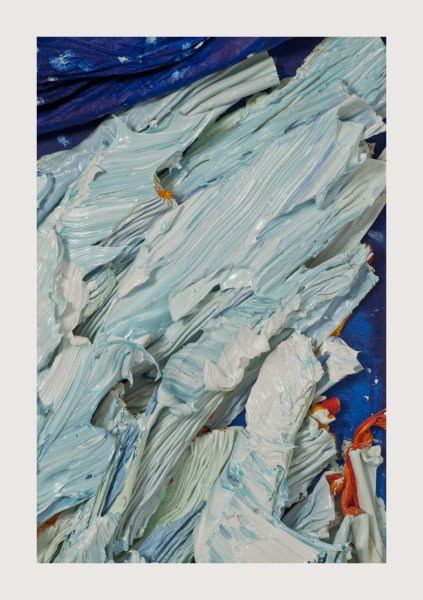

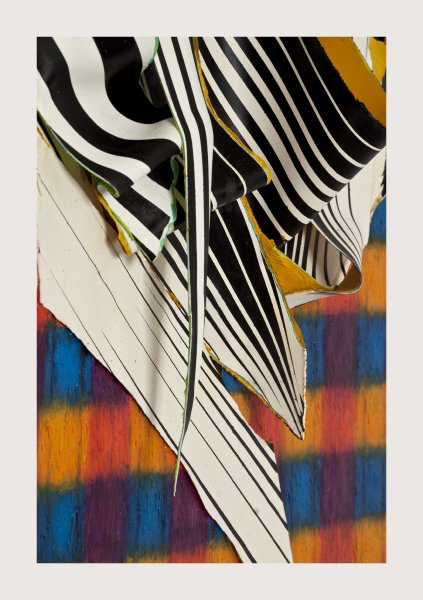

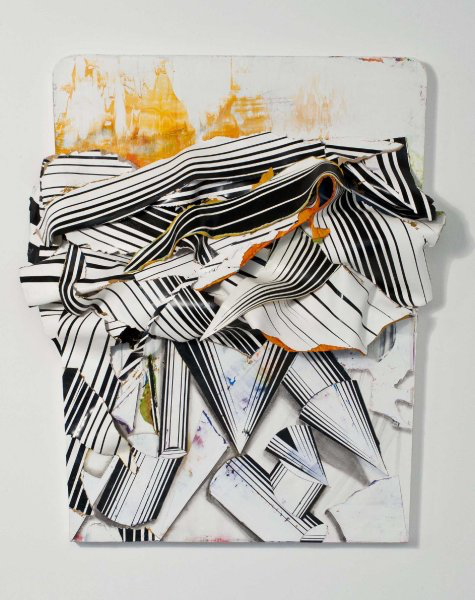

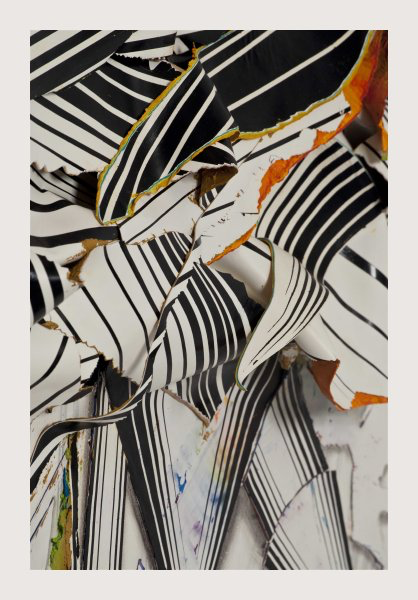

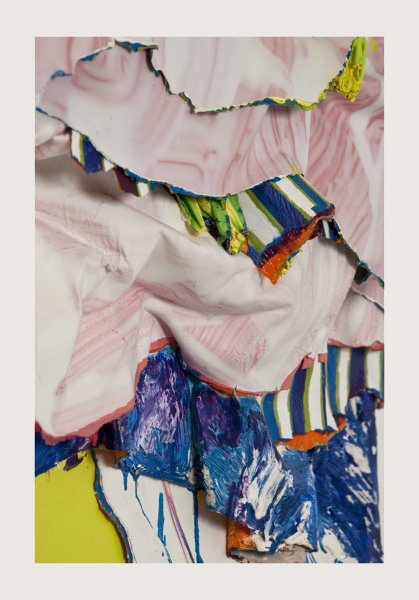

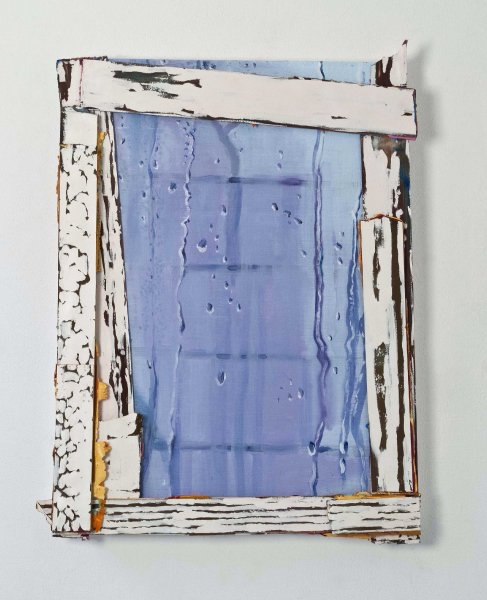

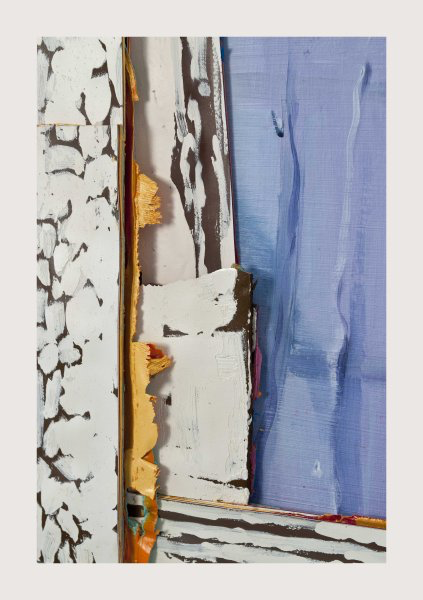

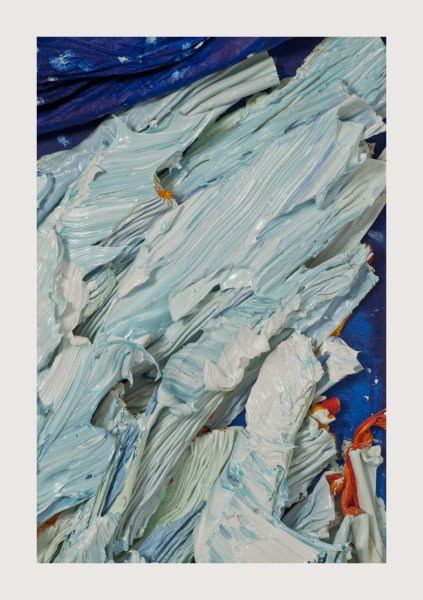

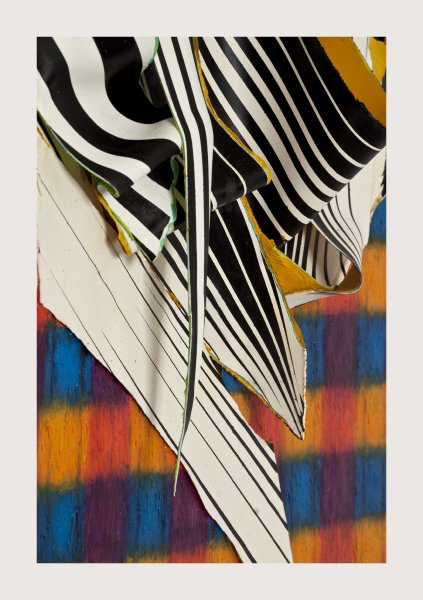

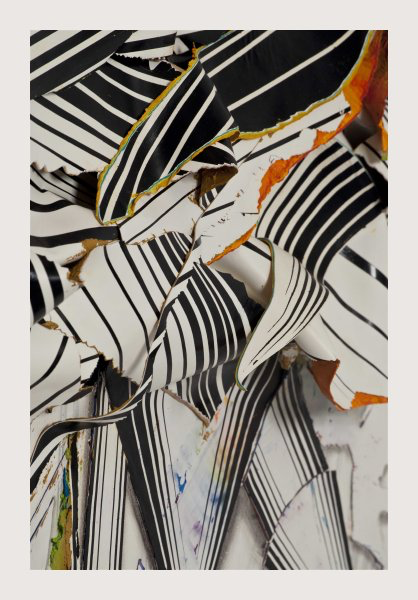

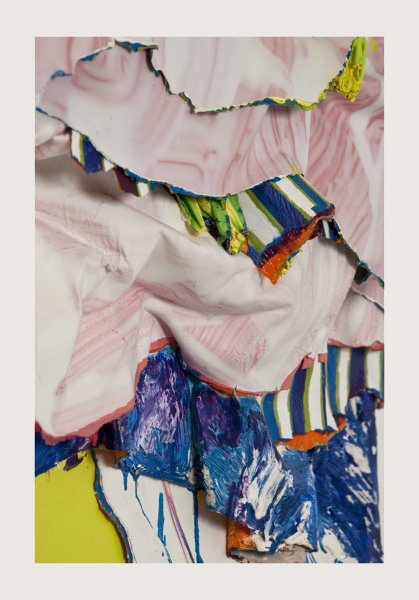

In Free Experience, I have returned to the figure-ground relationship as a way of exploring the range of possibilities for the representation of an illusion in as many different ways as possible, from tromp-l’oeil to verisimilitude, while still remaining undeniably within the confines of a traditional painting. These paintings are a collision of abstraction and representation, of illusion and three-dimensional form.

Looking at art is a free experience. It costs you nothing. But it should also be an experience that is free from encumbrances, one that inspires you to see the world as if for the very first time. But perception is a tricky thing. It is never without personal history. How do we see, what do we think we see? What makes the phenomenological experience of looking at something, particularly a work of art so compelling?

The seductive nature of that mystery is what drives my exploration in this new body of work.